There is so much unkindness in the world. People act like bullies online, with no consideration that there might be a human being on the other end. We’ve lost the ability to discuss our disagreements in a civil and kind manner, and it makes me so sad. But good people all over the world can change that if we just take the time to understand each other and choose kindness instead of judgment and patience instead of indignation–if we choose to love instead of be offended and give everyone the benefit of the doubt before jumping in to condemn them.

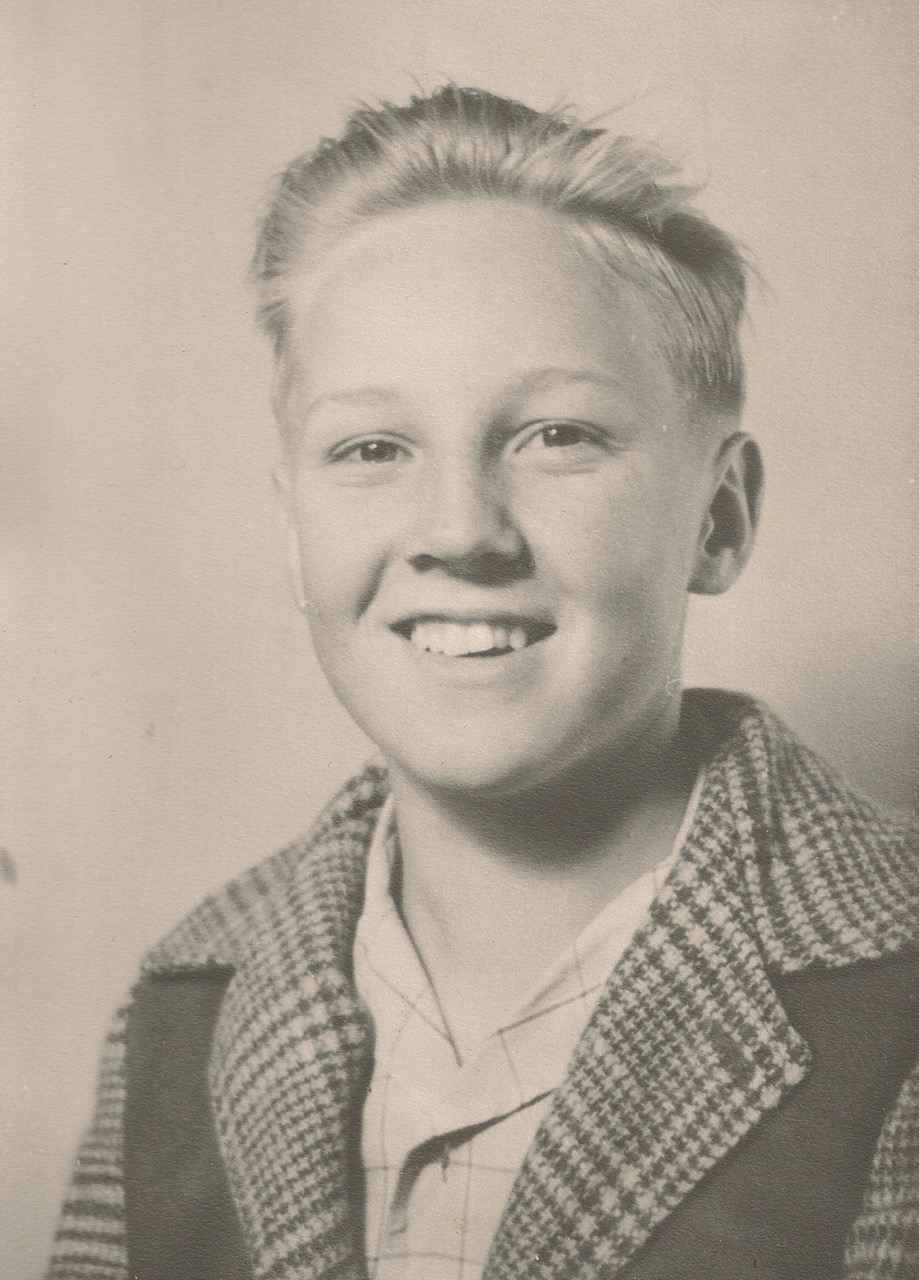

Here is a story of love and kindness from my dad, Richard Gappmayer. It proves that we can treat even our bitterest enemies with kindness and that kindness will come back to us. “Cast thy bread upon the waters, for thou shalt find it after many days.” Eccles. 11:1

In 1945 near the end of WWII, German prisoners of war were given the option of staying in a POW camp in North Africa or coming to different parts of the US to work on American farms. These men were officers who could not be required to work, but life for them in the States picking cherries was better than a POW camp in North Africa. There was an internment camp in my town on the site that is now occupied by a junior high school.

Farmers in our town could hire these German men to work on their farms. My father owned 30 acres of fruit trees, and he would arrange to get ten prisoners to help harvest fruit. He would pick them up at the camp in the morning and bring them to the cherry or other fruit orchard, and they would harvest the fruit. A guard was sent with them the first year they were here. He would usually sit under a cherry tree and go to sleep. There was no worry about the POWs escaping because life was better for them here in a prisoner of war camp than in Germany or any other place affected by the war. My responsibility was to carry drinking water to the pickers and to keep them supplied with cherry boxes.

I remember one time when the men talked me into stealing the sleeping guard’s rifle and hiding it in a tree. When he opened his eyes, I was standing there with, I am sure, a very guilty look on my face. He realized that his rifle was gone and he, for a few seconds, looked confused. He soon assumed that I was the culprit, and he began to yell at me some very inappropriate words and threats that I can’t repeat. The POWs were observing all of this and were getting a big kick out of it. The guard told me that if I did not return his rifle, he would strangle me. [SMILE] He looked very serious, so I told him that if he would give me a quarter, I would find his rifle. He appeared to realize that giving up a quarter was better than being court martialed for losing his weapon. So, I climbed the tree and retrieved his rifle. By the second year, guards were no longer sent with the prisoners.

The US government provided lunch for the prisoners: it consisted of black bread, cold cuts, and luke-warm tea. My mother thought this was completely inadequate for men working on a farm, so every day, she made a big pot of soup and homemade bread, which I served to the prisoners. We also had a cow which my father or older brother would milk. We saved up the cream for a week, and then I would churn it into butter. One day I took a large plate of this homemade butter out where these men were eating. I set it on the table, and they all stared at it. One of them asked me, “Richard, what is this?” I responded, “butter.” He said, “From the cow?” “Yes”, I said. It did not seem like anything unusual to me, but it did to them. Germany had been so poor for so long that many of them had not eaten butter for several years, and some of them had never tasted it at all. One of the Germans carefully and very geometrically cut the butter into 10 equal parts so each prisoner could have exactly the same amount. They licked the platter clean. Even though these men were prisoners, my parents wanted to share with them whatever our farm produced, even something as simple but precious as butter.

Most of these men were college graduates. Some of them could speak English, and they liked to practice their English on me or anyone else. I learned a few German words, but I get them confused with the half-dozen Spanish words that I know. My father joked with the German POWs and tried to make them feel welcome and needed. Dad would communicate with these men with much arm waving and saying words that he thought sounded like German. He thought that they understood because they responded by laughing and nodding their heads. He showed a real interest, respect and concern for these men, both in words and actions, and they appreciated it. He would arm wrestle with them, tease them, and they loved it.

My father joked with the German POWs and tried to make them feel welcome and needed. Dad would communicate with these men with much arm waving and saying words that he thought sounded like German. He thought that they understood because they responded by laughing and nodding their heads. He showed a real interest, respect and concern for these men, both in words and actions, and they appreciated it. He would arm wrestle with them, tease them, and they loved it.

They worked in our town for two summers, 1945 and 46. After the fruit was harvested in the fall, they went to Texas to pick cotton. In 1946, the war was over, and they were sent back to Germany, no longer prisoners. My sister, Beatrice, and my father corresponded with some of them and maintained contact with only one, Kurt Treiter.

The Korean War was winding down in 1955. I was drafted and thought that I would be going to Korea, but I was sent to Germany instead. My sister told Kurt Treiter in a letter that I was in Bad Krueznach, a city in Southern Germany. One day when I was lounging in the barracks, a request came over the public address system: “Richard Gappmayer, you are wanted at the front gate.” We would hear this announcement from time to time. It was Kurt Treiter. He lived nearby in Limburgherhoff and had come to see me. He invited me to come to his home and meet his wife and daughter. He provided me with train tickets and directions. I went there on a Sunday afternoon. I knocked on the door, and it was opened by a very cute little girl who curtsied and said, “Welcome to our home.” Her name was Ingrid, and she was eight years old and the only child of Kurt and his wife. They treated me like royalty. After a very good meal, we went to the local park, which seemed to be the custom. The park was full of their friends and neighbors, and I was introduced to all of them. Kurt related our relationship, and they all seemed to be very interested.

After I returned from Germany, I stayed in contact with the Treiters. When I told them that I was marrying my beautiful wife, Anne, they sent us a golden tea set, which we still have. And when I announced to them the birth of our oldest daughter, they sent us a beautiful, hand-knitted sweater, booties, and hat.

About ten years later, my sister, Beatrice, and her husband Max went to Germany and visited with the Treiters. By then, Ingrid was grown up and married. She and her husband became good friends with Beatrice and Max. The four of them spent time together touring Southern Germany.

This is a wonderful example of what can happen when people are kind to each other and treat each other as human beings instead of enemies.

Great story! I wish my dad had had more contact with the POWs in Wisconsin.

Yes, Terri, it’s interesting how these POWs were sent to the most random places and few people know about it.